Old Earth Ministries Online Geology Curriculum© Old Earth Ministries (We Believe in an Old Earth...and God!) NOTE: If you found this page through a search engine, please visit the intro page first.

|

|

Geology - Chapter 3: Minerals

|

Lesson Plan

Monday - Read Text Tuesday - Research Wednesday - Quiz Thursday - Review Friday - Test

|

|

Parents Information This lesson plan is designed so that your child can complete the chapter in five days. The only decisions you will need to make will be concerning the research task for Tuesday. It is up to you to determine if the student will simply fill in the answers, or provide a short essay answer. You will also need to determine the percentage that this research will play in the overall chapter grade, if any. |

|

|

Molecular Structure As you know, atoms

are the basic building block of molecules. The study of minerals,

known as mineralogy, is a study of their molecular structure. For

example, the common mineral

quartz is

made of the molecule SiO2, which contains one atom of silicon and

two atoms of oxygen. Throughout this chapter, we will use quartz as an

example to illustrate the various Definition By definition, a mineral is...

A short way of saying the definition of a mineral is...

Although minerals fit the above definition, there are variances. One of the most important ways that minerals can be altered is known as ionic substitution. In ionic substitution, two or more kinds of ions can substitute for each other in a mineral structure. For example, the group of minerals known as olivine have the formula (Mg,Fe)2SiO4. The ions of magnesium (Mg) and iron (Fe) can substitute for each other freely. In this way, you have minerals with different properties, yet the same basic chemical formula. Physical Characteristics Minerals exhibit different physical characteristics based on their composition. It is these physical characteristics that makes many minerals identifiable simply by doing a routine examination without any sophisticated equipment. A. Color. When you

first examine a rock, you probably note its color first.

B. Streak. The color of a mineral in powder form is called a streak, and the streak is usually more diagnostic than the color of the crystal itself. One of the simple tools you can buy is a streak plate, which is a small (2x2 inches) unglazed ceramic plate. There is even a website where you can enter the streak color, and it helps you identify the mineral. One of the best examples for the usefulness of a streak plate is gold and fool's gold (pyrite). Real gold has a gold streak. Pyrite, although it looks like gold, produces a black streak. Our quartz sample would leave a white streak. One important point to remember, though...you can only streak items that have a hardness of 7 or less, which leads us to the next physical characteristic. C. Hardness. The hardness of a mineral is a measure of the mineral's resistance to abrasion. Hardness is frequently used in the field to test mineral samples, and you can easily purchase a mineral hardness kit. The hardness scale runs from 1 to 10, and was devised by a German mineralogist, Friedrich Mohs. It is known as the Mohs scale of hardness. Here is the complete scale.

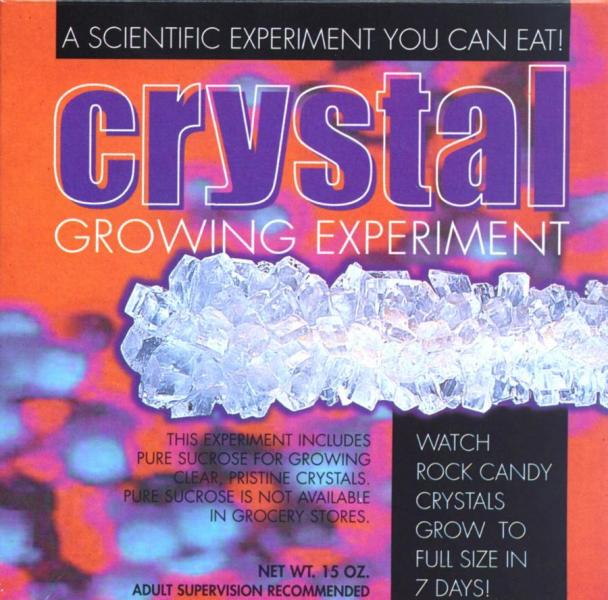

If you have a hardness kit, you can use the various minerals in it to test your sample. Once you determine the right hardness of your sample (after you have its color and streak), you can look up all the minerals of that hardness, color, and streak combination, and you could be close to identifying the mineral! Other hardness values include your fingernail (2.5), a copper penny (3.5), a knife blade (5.5), window glass (5.5), and a steel file (6.5). D. Crystal Form. Minerals develop crystal faces with a specific geometric form. The shape of a crystal is governed by its internal molecular structure. Quartz, for example, forms a six-sided prism ending in a 6-sided pyramid. The study of crystals is known as crystallography. There is a complete system of classification for crystal shapes, and there are a total of 32 distinct crystal classes. If you want to examine the 32 crystal classes, see Crystallography and Minerals Arranged by Crystal Form. E. Cleavage. Cleavage is the tendency of a crystal to split or break along smooth planes parallel to zones of weak bonding in the crystal lattice. If a crystal breaks, and the surface is irregular, it is said to show a fracture. If it breaks along surfaces related to the crystal structure it is said to show cleavage. The quality of the cleavage can vary, and is described with words such as "perfect," "good," "distinct," and "indistinct." The mineral may show cleavage in more than one direction, but the number and direction of the cleavage planes in a mineral species are always the same. Some minerals, such as quartz, have no cleavage. If you broke a quartz crystal, it would be said to fracture. Quartz exhibits a type of fracture known as a conchoidal fracture. It has curved surfaces, similar to broken glass. To learn more, see Cleavage and Conchoidal fracture. F. Specific gravity. Specific gravity is the ratio between the weight of a given volume of the mineral and the weight of an equal volume of water. For example, the specific gravity for quartz is 2.65. That means that one cubic inch of quarts weighs 2.65 times as much as one cubic inch of water. Specific gravity is normally determined in a laboratory, although you could make crude measurements in a home lab. You would need a weight scale to weigh the mineral, and also a graduated beaker. First, weight the mineral. Then fill the beaker with water to one of the lines, and record how much water you have. Place the mineral inside the beaker, and take another measurement. Subtract the first measurement (water only) from the second measurement. This will give you a rough estimate of the volume of the mineral. Next, calculate the weight of an equal volume of water, and then you can calculate the ratio. To learn more, see specific gravity. Crystals grow when matter changes from a gaseous or liquid state to a solid state, and they are destroyed when they are heated. An easy way to picture this is with volcanic lava. As the lava cools, crystals can form. The longer it takes for the lava to cool, the larger the crystals become. Material that cools quickly produces small crystals...sometimes so small that you cannot see them with the naked eye. The process of

crystal growth is called crystallization. Typically,

crystals grow from a melt (also called a "solution").

A melt is simply molten rock. As the melt cools, many different

crystals can grow at the same time. For instance, suppose a melt was

at 2,000 degrees centigrade. Quartz has a melting point

of 1650 degrees. As the melt Other Properties There are several other properties that you can use to identify a mineral.

Silicate Minerals By far the most

important minerals on earth are the silicates. Silicates

To see an animation of the silicate mineral structure, click here. End of Chapter Make an index card for each of the ten minerals in the Moh's scale of hardness. On each card, list the mineral's characteristics, such as color, streak, hardness, crystal form, cleavage, specific gravity, magnetism, fluorescence, etc. You can use these cards as study aids, and you may wish to continue the practice as you study rocks in the following chapters. Today you will complete an 10 question practice quiz. The link to the quiz will open a new window. You can come back here and check your answers. Do not click the Back button on your browser during the quiz. After the quiz, continue your research project, if necessary. Please review the terms in bold in the text, and ensure you have completed your research work from Tuesday. Today you will take the end of chapter test. Please close all other browser windows, and click on the link below. During the test, do not click on the Back button on your browser. After you have completed the test, you may proceed to the next chapter on your next school day. Please return to the introduction page for the link to the next chapter. Return to the Old Earth Ministries Online Geology Curriculum homepage. Helpful Links

Mineralogy Database (webmineral.com) Amethyst Galleries' Mineral Gallery Mohs Scale of Hardness (Wikipedia)

|

principles of a mineral.

principles of a mineral.

compose up to 95 percent of the volume of the earth's crust. Silicate

minerals are complex, but they all contain a basic building block called the

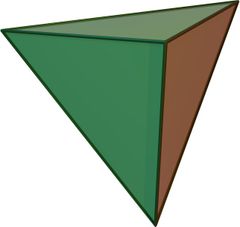

silicon-oxygen tetrahedron. This is represented by the

formula (SiO4)-4, in which four large oxide ions (O-2)

are arranged to form a four-sided pyramid with a smaller silicon ion (Si+4)

fitted into the cavity between them. There are two ways in which

silicate minerals are formed. First, the oxygen ions of the tetrahedra

form bonds with other elements, such as iron or magnesium. An example

of this is the mineral olivine. The second way silicate minerals

are formed is by the sharing of an oxygen ion between two adjacent

tetrahedra. Thus, the two tetrahedra form a larger ionic unit.

Different arrangements of the shared ions results in the four major silicate

mineral groups.

compose up to 95 percent of the volume of the earth's crust. Silicate

minerals are complex, but they all contain a basic building block called the

silicon-oxygen tetrahedron. This is represented by the

formula (SiO4)-4, in which four large oxide ions (O-2)

are arranged to form a four-sided pyramid with a smaller silicon ion (Si+4)

fitted into the cavity between them. There are two ways in which

silicate minerals are formed. First, the oxygen ions of the tetrahedra

form bonds with other elements, such as iron or magnesium. An example

of this is the mineral olivine. The second way silicate minerals

are formed is by the sharing of an oxygen ion between two adjacent

tetrahedra. Thus, the two tetrahedra form a larger ionic unit.

Different arrangements of the shared ions results in the four major silicate

mineral groups.